WipEout: How a Futuristic Racing Game Defined the PlayStation Era

The Racer That Turned PlayStation Into a Cultural Moment

WipEout: A Friend In Speed

Let’s get one thing straight: when WipEout hit in 1995, no one quite knew what the hell it was doing, and that was exactly the point. This wasn’t your grandad’s racer. Hell, it wasn’t even your older cousin’s racer. This was a game that screamed futuristic adrenaline, with neon-soaked visuals, pounding techno, hover-ships that felt like caffeinated skateboards, and track designs that punished you brutally for thinking like a sane, responsible adult.

At a time when most racing games were still very much about tyres, asphalt, and pretending you understood gear ratios, WipEout turned up and asked: “What if the ground was optional, the speed was borderline irresponsible, and the soundtrack sounded like it came straight from a warehouse rave at 3am?” And then it actually pulled it off.

What made WipEout special wasn’t just that it was fast. Plenty of games were fast. It was that it felt modern in a way games rarely did back then. The PlayStation itself was new, edgy, and clearly aimed at people who wanted something cooler than a Saturday morning cartoon vibe, and WipEout became the perfect poster child for that attitude. It looked like the future, sounded like the future, and marketed itself like the future: sharp lines, bold typography, and a confidence that bordered on arrogance.

Decades later, WipEout isn’t just a franchise, it’s a snapshot of the 1990s gaming zeitgeist. It lives somewhere between rave culture, graphic design experimentation, early 3D hardware flexing, and that very specific mid-’90s belief that the future would be loud, angular, and glowing with neon at all times. It sits right alongside early PlayStation adverts, The Designers Republic artwork, and big-beat soundtracks as part of a very deliberate cultural moment.

And the wild thing is, it wasn’t just style doing the heavy lifting. Beneath the flashing lights and thumping bass was a genuinely demanding racing game. One that asked you to learn tracks at terrifying speeds, master airbrakes that barely made sense at first, and stay calm while everything on screen screamed at you to panic. WipEout didn’t hold your hand. It slapped it away and told you to get faster.

Over the years, the series evolved, refined itself, jumped platforms, embraced HD, flirted with handhelds, and eventually ran straight into shifting priorities inside Sony. The studio behind it, Psygnosis (later Studio Liverpool), would eventually be closed, leaving WipEout as one of gaming’s great “what if?” stories. What if it had continued? What if it had grown alongside modern hardware instead of being preserved mostly through remasters?

So this isn’t just a nostalgia trip. This is the story of WipEout: where it came from, why it mattered, how it evolved, and why people are still talking about a futuristic racing game from 1995 like it never really left.

Right. Let’s do this properly.

From Pub Chat to Pedal-to-the-Metal

The origin of WipEout is almost too absurdly British to be true — but it is. According to the people who were actually there, the initial spark didn’t come out of a boardroom, a market research report, or some corporate brainstorming session. It came out of a pub conversation in Oxton, Merseyside, with Psygnosis designers Nick Burcombe and Jim Bowers throwing ideas around over drinks.

Anti-gravity racing came up. So did the idea of pushing speed way beyond what was normal at the time. Somewhere in that conversation was a thought that would end up reshaping PlayStation’s early identity: what if racing games didn’t have to behave?

There’s a real Super Mario Kart influence in there too — not visually, but philosophically. Kart racing proved you could mix speed with chaos, tight tracks with weapons, and still have something that felt skill-based. WipEout took that structure and asked an unhinged follow-up: “Okay, but what if it was faster, sharper, less forgiving, and looked like the future was actively trying to kill you?”

A pub chat alone doesn’t give you a genre-defining game. What made this one different was who was having the conversation.

Psygnosis already had a reputation. Through the late ’80s and early ’90s, they’d built one on the Amiga by doing things other studios simply couldn’t, or wouldn’t: technical ambition, experimental design, and a willingness to push hardware until it squealed. This was the studio behind games like Shadow of the Beast and Lemmings, titles that were as much technical showcases as they were games you actually played.

So when Sony came knocking with this new thing called the PlayStation — a console built from the ground up for 3D — Psygnosis was perfectly positioned to do something interesting with it. WipEout wasn’t just “another racer” for the launch lineup. It was a deliberate attempt to show what Sony’s hardware could do when you stopped treating it like a souped-up 16-bit machine and started treating it like a proper 3D platform.

And that mattered, because early 3D was often… rough. Cameras fought you. Frame rates dipped. Games looked like they were made of doorstops. WipEout still had the chunky polygons of its era, obviously, but it used them intelligently: clean track silhouettes, strong visual language, and speed that felt intentional rather than accidental.

If you squint, you can see the DNA of earlier Psygnosis experiments in there, including Matrix Marauders, a prior game that played with hovering units and momentum. But WipEout took that technical thinking and wrapped it in something far more cohesive, far more confident, and far more stylish.

And the style wasn’t accidental. The visual identity was shaped with The Designers Republic (alongside Psygnosis’ own internal art direction), and their sharp typography, bold iconography, and corporate-futurist vibe helped define not just the game, but the entire brand around it. The teams looked like actual teams. The logos looked like they belonged on real merchandise. The menus looked like they’d been designed by someone who owned more than one black turtleneck.

Musically, WipEout was just as deliberate. The original game combined music by Tim Wright (CoLD SToRAGE) with licensed electronic tracks from major artists of the era. It didn’t sound like “game music that tries to be electronic”. It sounded like someone nicked a stack of club records and built a racing game around them. That decision did a huge amount of heavy lifting for the series’ identity — and it also set a bar that the sequels would have to clear.

So no, WipEout wasn’t just born in a pub. It was shaped there, then refined by a studio with the technical chops and cultural awareness to turn a slightly mad idea into something iconic.

It Begins: WipEout (1995) - A Sensory Overload in Motion

Released on 29 September 1995 as a European PlayStation launch title, WipEout didn’t just arrive with the console, it helped define what that console even was. This wasn’t “here’s a decent racer you can pick up on day one.” This was Sony planting a flag and saying, this is what the PlayStation stands for.

And it landed at exactly the right time. 1995 was a messy transitional moment. The jump to 3D was happening, but not gracefully. Early polygon games often looked awkward, ran poorly, or felt like 2D design being dragged kicking and screaming into a third dimension. WipEout didn’t just embrace 3D; it committed to it, and then wrapped it in an aesthetic that made the limitations feel like a deliberate choice.

The game was set in 2052, placing you in the fictional F3600 Anti-Gravity Racing League. You weren’t driving cars; you were piloting hovering craft skimming above the track at absurd speeds, held down by magnets and optimism.

And that was a big deal at the time.

Because most racers in the mid-’90s were still about realism, or at least the illusion of it. Braking zones you could actually understand. Weight transfer you could pretend you felt. WipEout threw a lot of that out. The tracks were wide but unforgiving, full of turns that demanded commitment rather than caution. Hesitate and you were in the wall. Overcorrect and you were in the wall with extra enthusiasm.

Then there were the weapons. Pickups scattered around the track gave you rockets, mines, shields, speed boosts, and other tools of chaos. Suddenly, racing wasn’t just about hitting apexes. It was about survival. You could be flying the cleanest lap of your life and still get erased by a well-timed hit from someone behind you.

Mechanically, the handling was floaty in all the right ways. The craft didn’t snap; they glided and slid, giving you just enough control to feel skilled while constantly threatening to take it away. It had that great early-arcade thing where you start off thinking, “This controls like shopping trolley physics,” and then two hours later you’re threading corners like you’re doing keyhole surgery at 500 mph.

Once you started understanding how airbrakes worked, how to scrub speed without killing momentum, and how to set up for the next corner instead of the current one, the whole game clicked. The sense of speed wasn’t just visual; it was structural. The camera, track flow, and visual language were all tuned to make your brain panic slightly. It was controlled chaos, and every race felt like you were one mistake away from disaster.

Put all of that together and WipEout felt less like a traditional racer and more like an interactive sensory overload. You didn’t master it with gentle improvement. You mastered it by learning exactly how much speed you could get away with before the wall taught you otherwise.

For a launch title, that was a hell of an introduction.

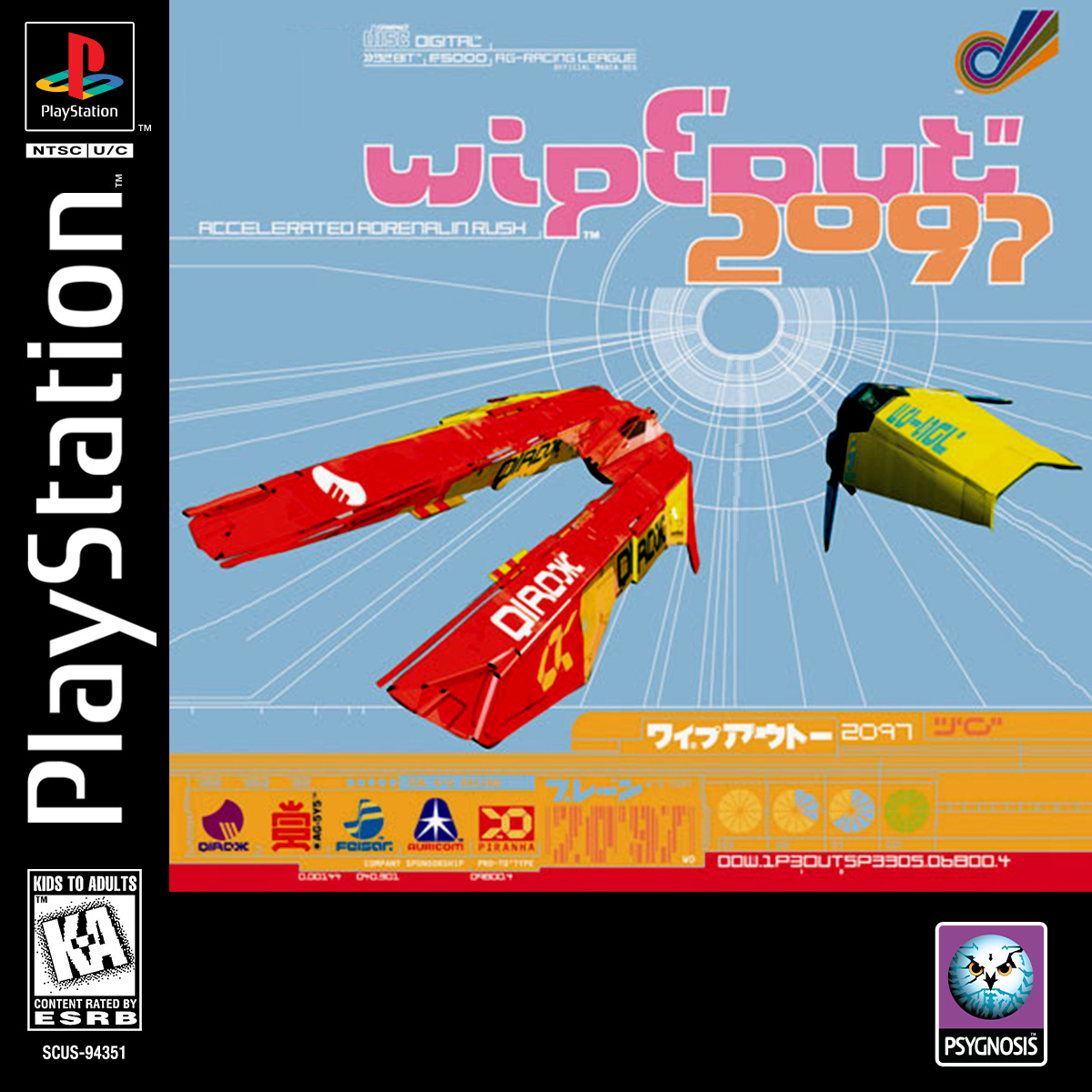

The Crowning Glory: WipEout 2097/XL (1996)

If the original WipEout was a statement, WipEout 2097 was the manifesto, printed in bold type and thrown at your face at illegal speeds.

Released in 1996 (and branded as Wipeout XL in North America and Japan), 2097 didn’t just iterate on the original. It refined it. This was Psygnosis looking at their debut, identifying every rough edge, every limitation, every “yeah but imagine if…” moment, and fixing it with intent.

Where the original sometimes felt a little wild, 2097 felt focused. The handling tightened up. The ships had more personality. The difficulty stayed brutal, but it was brutal in a way that felt fair. When you crashed, you usually knew exactly why — which is the key difference between “hard” and “cheap”.

One of the biggest changes was the move to the F5000 league, replacing the F3600 class. Translation: faster, meaner, more demanding. These weren’t races you reacted to. These were races you anticipated. Corners had to be memorised. Lines had to be planned. Hesitation wasn’t punished; it was rejected.

Tracks got slicker and more readable, but also more demanding. Straights lulled you into confidence and then fed you into turns that required absolute commitment. The game demanded that you trust the physics, trust the airbrakes, and trust yourself — usually in that order.

The weapons grew up too. Combat felt more tactical, and energy management mattered more. You couldn’t just brute-force your way through races purely on speed; survival became part of the strategy. Winning wasn’t just finishing first. It was finishing alive.

But 2097 didn’t become legendary just because it played better.

It became legendary because of how it felt.

The Designers Republic’s influence was everywhere, from team logos to menus to track branding. Every team felt like a real entity with identity and history. It didn’t feel like “levels”. It felt like a future sport with its own culture.

And then there was the soundtrack. 2097 went bigger on licensed electronic music, with a broader roster of high-profile artists. It didn’t treat music as background decoration. It made it part of the identity, part of the speed, part of the attitude.

Critics loved it. Fans loved it. Even people who normally bounced off futuristic racers looked at 2097 and said, “Okay, I get it now.”

For many, this is where WipEout peaked — not because the series stopped being good afterward, but because 2097 hit that perfect intersection of technology, culture, and confidence that doesn’t come around often.

The Refinement: WipEout 3 (1999), Farewell to the PlayStation 1 Era

By the time WipEout 3 arrived in 1999, the PlayStation was no longer the scrappy new kid trying to prove itself. Developers understood the hardware. Players understood 3D. Psygnosis understood exactly what WipEout was supposed to be.

So instead of reinventing the series, WipEout 3 did something harder: it refined it.

It wasn’t a loud revolution like 2097. It was a confident tightening of the screws. The presentation was sleeker, the UI cleaner, the whole thing sanded down without losing the attitude.

A huge structural win was the three speed classes: Venom, Rapier, and Phantom. Venom eased newcomers in, Rapier delivered the classic pace, and Phantom was pure terror. The kind of speed where you weren’t racing the track so much as predicting it.

Handling was subtly reworked. Ships felt heavier and more planted at high speed. Airbrakes were easier to understand. Collisions felt less random. Success relied more on clean lines and consistency than chaos.

Track design followed the same philosophy. Circuits were wider and more readable, with smoother flow and better visual cues. Still punishing, just fairer about it. Weapons were rebalanced too: still dangerous, still capable of ruining your day, but less dominant. Racing skill took centre stage again.

Visually, WipEout 3 was late-generation PS1 development at its best. Psygnosis squeezed everything they could out of the hardware, delivering one of the most polished racers on the system. It’s a fitting farewell to the PS1 era, not because it shouts the loudest, but because it sounds like a series fully comfortable in its identity before stepping into the uncertain reality of a new generation.

The Late ’90s and Early 2000s: All the Platforms, All the Races

By the late ’90s, WipEout had escaped the confines of being “that cool PlayStation racer” and turned into a recognisable brand. And once that happens, the next step is obvious: put it everywhere.

Some of those places made sense. Others raised eyebrows.

Case in point: Wipeout 64.

Released in 1998 for the Nintendo 64, it was the most awkward family reunion in WipEout history. A series so closely tied to PlayStation suddenly showing up on Nintendo hardware felt borderline illegal. Sony wasn’t thrilled. Fans were confused. And yet, it existed.

It wasn’t a lazy port either. It had original tracks, its own feel, and tried to make the most of the N64 controller. But culturally, it always felt slightly off. The N64’s vibe didn’t perfectly match WipEout’s sleek, club-futurist identity. It’s one of those games that’s easier to appreciate as a “wait, they actually did that?” footnote than as the natural home of the series.

Then came the jump to the next generation.

In 2002, WipEout Fusion arrived on the PlayStation 2, and this is where things got complicated. Fusion wasn’t bad. It was different. It took bigger swings with leagues, handling, and progression, and that was enough to split opinion. Some fans appreciated the experimentation. Others felt the series had drifted from its razor-sharp identity.

It didn’t help that the PS2 era was overflowing with racers. WipEout was no longer the uncontested futurist speed king. It was still stylish. Still fast. It just wasn’t alone anymore.

Behind the scenes, this era marked a studio transition too. Psygnosis was now fully under Sony and operating as Studio Liverpool. The team was still there, but expectations had changed.

Rather than doubling down on consoles, Studio Liverpool made a smart pivot to handhelds.

In 2005, WipEout Pure launched alongside the PSP and surprised everyone by feeling like a full series entry, not a compromised portable cousin. Tight handling, great visuals for the hardware, and track design that proved anti-gravity racing could thrive on a smaller screen. Pure also leaned into downloadable content early, extending its lifespan in a way that felt genuinely forward-thinking.

Then in 2007, WipEout Pulse locked the PSP era in place. It refined the handling further, expanded the modes, pushed the hardware harder, and cemented the PSP entries as core WipEout, not side projects. A lot of what people now think of as “modern WipEout” traces straight back to Pure and Pulse: the feel, the progression, the way track readability and speed are balanced so you feel in control even when you’re absolutely not.

By the mid-2000s, WipEout wasn’t just surviving. It was adapting.

The HD Era and the Omega Revival

By the late 2000s, gaming had entered its high-definition obsession phase. “Next-gen” meant resolution numbers, frame rates, and buzzwords, and WipEout was perfectly positioned to benefit.

In 2008, WipEout HD arrived on PS3 as a digital-first release on PlayStation Network. That wasn’t just a distribution detail; it shaped the whole product. This wasn’t a bloated sequel trying to be everything. It was a focused take on what WipEout needed most: clarity, responsiveness, and presentation that could keep up with the speed.

HD rebuilt content from the PSP lineage for home consoles, reworked for HD displays with cleaner geometry, sharper presentation, and performance that made the game feel incredible to play. It later received HD Fury in 2009, adding more tracks, more ships, and a combat-focused mode that leaned harder into weapons. (And yes, HD did eventually get a physical release in some regions after the initial digital launch.)

The series’ core strengths benefited massively. Higher-speed classes became more readable without becoming easier. Zone Mode, in particular, felt like it had been made for this era: a pure test of nerve, reflexes, and how much you trust your own thumbs.

Then came the Vita.

In 2012, WipEout 2048 launched as a Vita title and served as a chronological prequel, linking back toward the original timeline. It was technically impressive, mechanically solid, and it ended up becoming the last mainline WipEout developed by Studio Liverpool.

Because later in August 2012, Sony closed Studio Liverpool, ending the original home of WipEout.

For a while, that felt like the end of the road.

Then, unexpectedly, WipEout came back in definitive form.

In 2017, WipEout Omega Collection released for PS4, bundling WipEout HD, HD Fury, and WipEout 2048 into one package and polishing the whole thing for modern hardware. It wasn’t just a remaster. It was the most comprehensive official “best of modern WipEout” collection Sony has ever put out.

And it reminded everyone how timeless the core formula really is. No live services. No battle passes. No seasonal chores. Just brutally fast racing, pristine presentation, and a skill ceiling high enough to keep you chasing perfection for years.

Omega Collection was bittersweet for fans. It felt like a celebration released long after the people who built the series were gone. If WipEout had to go quiet, at least it went quiet in style.

What Happened to Studio Liverpool?

This is the moment where WipEout stops being just a series history and starts becoming a cautionary tale.

Sony’s closure of Studio Liverpool in August 2012 was framed as part of a wider restructuring of its European studios. Regardless of the corporate reasoning, the loss landed hard. Studio Liverpool wasn’t just a team that made racing games. It was a studio with a specific identity: speed, precision, experimentation, and an obsession with presentation.

The sting is that this wasn’t a studio limping along. 2048 had just shipped. The talent was still there. The momentum was still there. Then it stopped.

Many of the developers moved elsewhere in the industry, but the concentration of experience and identity that made WipEout feel like WipEout scattered. Since then, the series has lived on mostly through remasters and compilations — brilliant ones, but still reflections of what already existed.

You can polish the tracks. You can remaster the ships. You can even strap it all to VR.

What you can’t easily replace is the studio that instinctively understood what WipEout was supposed to feel like.

That’s why Studio Liverpool’s closure still hurts. Not because the games stopped being playable, but because the future they were building toward never got the chance to arrive.

Final Thoughts

WipEout wasn’t just another racing franchise. It was a collision point where music, graphic design, bleeding-edge tech, and pure, unapologetic speed all smashed together and somehow didn’t fly apart.

Back in 1995, when most racers were still about tyres, traction, and pretending realism mattered more than fun, WipEout looked at all of that and said: “Cool. What if none of that applied?”

Instead of asphalt, you got hover-ships. Instead of engines, you got magnets and thrust. Instead of polite background music, you got electronic soundtracks that felt like they were trying to rewire your nervous system. It wasn’t just racing. It was attitude, confidence, and a specific vision of the future that felt dangerous in the best way.

And we bought into it completely.

We learned tracks corner by corner, crash by crash. We pushed Zone Mode until our thumbs hurt. We memorised racing lines not because the game told us to, but because survival demanded it. We played with the music turned up loud, convinced that going faster was always the correct answer.

That connection is why WipEout still matters. Plenty of classics get remembered fondly and then fall apart the moment you revisit them. WipEout doesn’t. Strip away the era and the branding and what you’re left with is still one of the cleanest, most satisfying high-speed racers ever made.

It dared to believe style and substance didn’t have to compete. That speed could be readable. That difficulty could be fair. That a racing game could trust its players.

If more studios had backed that kind of bold creativity, maybe we’d be talking about more mainline WipEout entries today instead of lovingly preserved remasters.

But here we are.

At least we still have Omega Collection, a near-perfect reminder of just how good this series was — and still is — when it’s allowed to be itself. Every time I boot it up, I remember why I fell for WipEout in the first place: because it feels like nothing else.

And maybe that’s why the dream hasn’t died.

All it would take is the right team, the right budget, and the courage to trust the formula again. The hunger is still there. The audience is still there. The future WipEout promised all those years ago? We never stopped wanting it.

So yeah. Maybe it never comes back.

But if it does, I’ll be there on the starting grid, music up, palms sweating, waiting for the countdown — hoping this time the future finally finishes the race.

We can only dream.